Lucky Charms

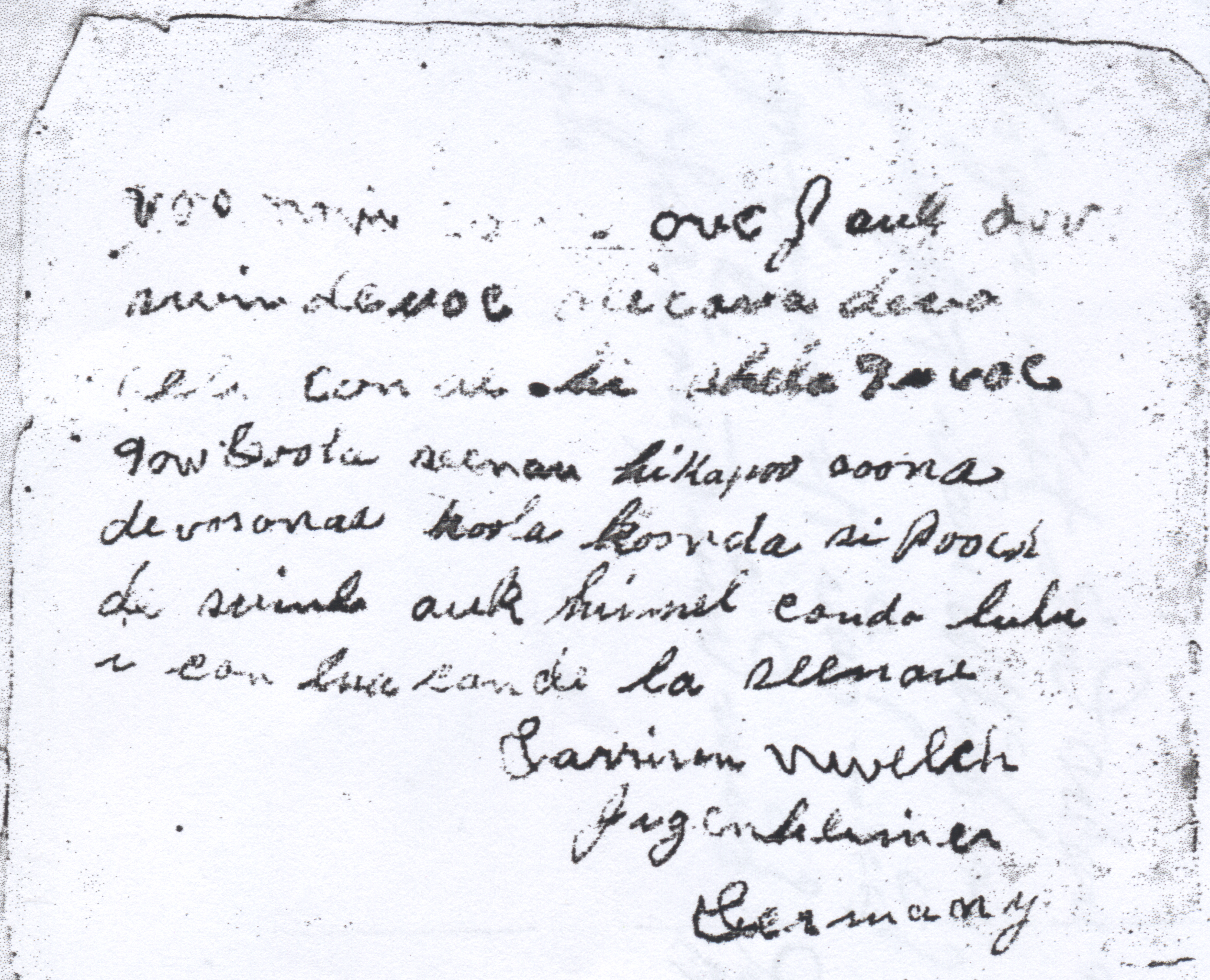

TWO MYSTERIOUS INSCRIPTIONS, believed to have been penned by Garrison Smith Welch (my 3x great grandfather), were found in a family Bible. The Bible sat in the home of one of Garrison’s great-grandsons—an 80-year-old farmer in Union County, Ohio (Robert E. Welch, d. 2010). When I first talked with him on the phone, he was surprised to learn that our Welches were believed to be of Irish descent, rather than German. Garrison’s father was Martin C. Welch, and according to the 1880 US Census, Martin’s father was born in Ireland. Old farmer Bob had figured they were German, because the inscriptions were written in some form of German. One of them was even signed by Garrison, followed by “Jugenheimer, Germany.”

The closest matching place name in Google Maps reveals a municipality called "Jugenheim in Rheinhessen.” Garrison’s wife, Susanna (née Bevelhymer), had descended from German immigrants. Her great grandfather had come from Saulheim, only 10 miles away from Jugenheim in Rheinhessen in the wine country of southwest Germany along the Rhine River. Could Garrison and his wife have visited her relatives there? Is his text even German

Written by two different hands, one of the inscriptions is Germanic; the other is enigmatic. I speak German, and both texts are difficult to pick apart, especially the one signed by Garrison. According to census records, Susannah could neither read nor write. She may have inherited the ability to speak some German, and this inscription looked as if it were possibly broken German, spelled phonetically, as if Garrison were taking dictation, as his wife recited it. Most of it, however, is foreign to me. So, I gave the inscriptions to a German friend, whose English is better than mine, who also speaks Dutch, French, and Spanish. Because he’s a doctor, he even understands some Latin. Here’s what he had to say:

Written by two different hands, one of the inscriptions is Germanic; the other is enigmatic. I speak German, and both texts are difficult to pick apart, especially the one signed by Garrison. According to census records, Susannah could neither read nor write. She may have inherited the ability to speak some German, and this inscription looked as if it were possibly broken German, spelled phonetically, as if Garrison were taking dictation, as his wife recited it. Most of it, however, is foreign to me. So, I gave the inscriptions to a German friend, whose English is better than mine, who also speaks Dutch, French, and Spanish. Because he’s a doctor, he even understands some Latin. Here’s what he had to say:

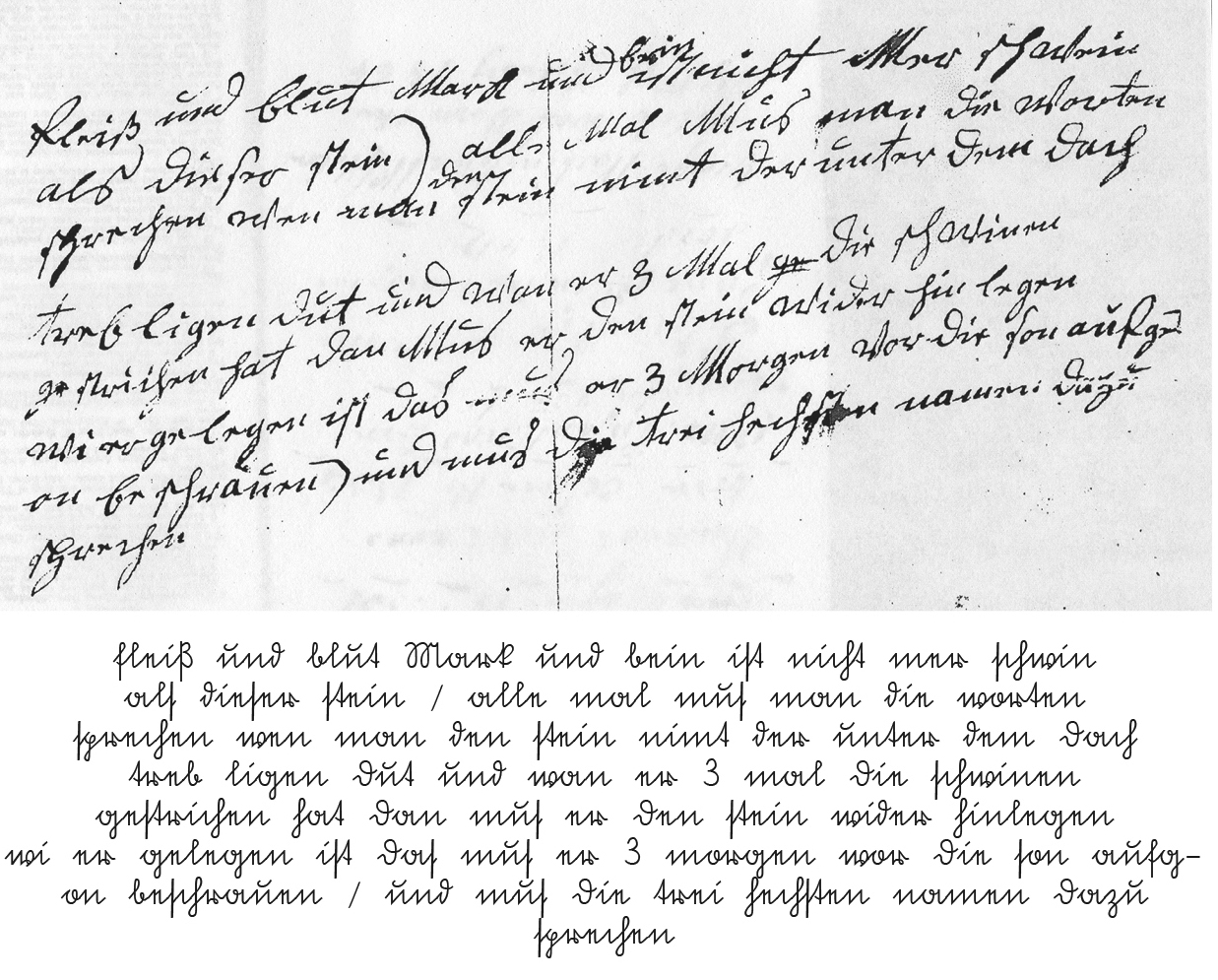

I've been able to decipher only the first text, the one written in old German handwriting. This is old southwest German, somewhat different from today's standard German. Spelling rules had not been standardized yet, it seems. The script-type used here is related to the old Courant-type standard German handwriting (Sütterlin script was a simplified version of this). It's a charm, possibly intended to heal diseased pigs (a disaster for these poor people back then). The charm is much older than the 1800s, I'm quite certain.

Fleiß und Blut Mark und Bein ist nicht Mer schwein

als dieser Stein / alle Mal Mus man die worten

sprechen wen man den Stein nimt der unter dem Dach

treb ligen dut und wan er 3 Mal die schwinen

gestrichen hat dan Mus er den Stein wider hinlegen

wi er gelegen ist das mus er 3 Morgen wor die Son aufg-

on beschrauen / und mus die trei hechsten namen dazu

sprechen

*Transliterated below (exactly as is from German to English)*

Diligence (Flesh) and Blood Marrow and bone is no More pig

than this stone / all times Must one the words

speak when one takes the stone which under the roof

staircase does lie and when he 3 times the pigs

has sweeped (stricken?) then he Must again lay down the stone

as it has been lying that must he 3 Mornings where the Sun ris-

en becried (announced) / and must the three highest names thereto

speak

Rheinhessen indeed lies in the southwest of Germany, where the Sütterlin writing style was said to be used. I Googled the term Sütterlin and found a downloadable font. Compare the translation in the image above—using that font—with the inscription.

Amazing, no? But what’s a charm doing in a Bible? Might the inscription give a clue that Garrison raised pigs (maps show he had a good plot of land for crops)? But what about the one signed by Garrison? What language is it, if not German? Could a farmer have been able to afford to travel overseas?

I will be looking for answers among linguists, pig farmers and pagan historians....